The legal system that developed in ancient Rome played a crucial role in the development of European law. In the modern legal systems of Europe and the Americas, the core legal terminology, many legal institutions, and the structure of presentation of material in legal codes and textbooks are derived from Roman law. In South Africa, it still survives as ancillary law, applied in cases not covered by modern legal norms.

Ancient Roman law is the most developed legal system of antiquity, serving as the foundation for the modern legal system. Roman jurists distinguished between public law and private law. The former relates “to the state of the Roman state,” while the latter relates “to the benefit of individuals” (according to the jurist Domitius Ulpian, 3rd century AD).

The fate of both branches of Roman law subsequently proved divergent. Roman public law did not outlive the Roman state and did not exert much influence on the state institutions of later nations.

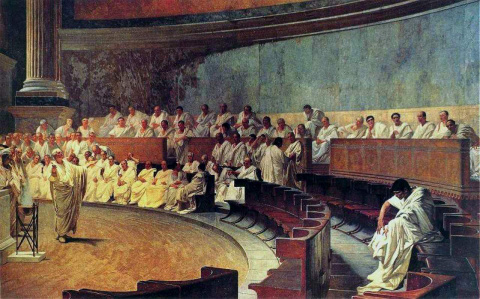

One can speak of the continuity of only some general principles of the republican period: a permanent parliament (such as the Roman Senate), a system of checks and balances, the election and accountability of officials to the people, parliament and the court, and the participation of the people in deciding the most important state affairs.

Roman private law, on the contrary, played a prominent role in the development of civil law in the Middle Ages and modern times. Roman private law formed the basis of the legislation of many Western European states, which either directly borrowed Roman legal concepts and institutions or adopted the principles of Roman law as models in developing modern codes (especially regarding property rights and contract law). The content of Roman private law extended far beyond the relations of a slave society and acquired a universal character.

The concepts developed by Roman lawyers, distinguished by the precision of their formulations and the clarity of their conclusions, formed the basis for the scientific development of modern civil law.

In many countries, Roman law forms the basis of professional legal education and, at the same time, of scholarly research in the fields of state and legal theory, as well as comparative law. Roman law is an outstanding monument of Roman culture and, at the same time, an integral part of modern European legal culture.

Roman law, the most developed system of ancient law, was formed and developed in ancient society, which offered broad opportunities (compared to other pre-industrial societies) for the development of private initiative and private property rights.

Roman law flourished during the early Roman Empire (late 1st century BC – early 3rd century AD), characterized by political and social stability, a high level of urbanization, and commodity-money relations. Unlike many other ancient societies, law in Rome emerged very early (as early as the Twelve Tables – 5th century BC) as a distinct system for regulating human behavior, distinct from religious and moral precepts.

In Ancient Rome, legal scholars first appeared in the world, and jurisprudence became a science (in the classical sense of the word) in the 2nd to 1st centuries BC. At its peak, Roman law was largely the result of the collaborative efforts of great Roman jurists. Many later jurists referred to Roman law as “the law of lawyers” and “written reason.”

Roman jurists divided law into public law, “relating to the status of the Roman state,” and private law, “relating to the benefit of individuals.” They devoted almost exclusively to the latter; and it was private Roman law that became the basis for the development of European law.

Private Roman law is characterized by highly developed individualism, the desire to provide optimal conditions for independent activity for every full participant in social and economic life, that is, first of all, for every Roman head of the family (large patriarchal family).

The works of Roman lawyers carefully and comprehensively developed methods for protecting the personal and property rights of individuals, legal concepts and structures relating primarily to property, inheritance and contractual law.

Drawing on their achievements in analyzing specific legal cases and the works of Greek philosophers (primarily Aristotle), Roman jurists created a legal language unmatched by any other legal system of the ancient world. After the collapse of the ancient world, Roman law gradually lost its former significance and fell into disuse. However, from the 12th century onward, Europe began to widely embrace and assimilate Roman legal heritage.

Since ancient times, people have entered into certain relationships with one another throughout their lives, most of which are regulated by legal norms and, accordingly, are called legal relations. The primary source of global legal culture is Roman civil law.

A significant portion of legal relations arose and arise in connection with the creation, acquisition, alienation, use, transfer of various property, etc.

One of the codifications of Roman law was Justinian’s codification, or Digest. The Digest, or Pandects, is a collection of excerpts from 2,000 works by 39 of the most prominent Roman jurists, primarily those who had the authority to officially interpret laws. The 9,200 excerpts are fragments.

The Digest is divided into 50 books, and the books are divided into titles (except for 30-32 books that have no titles). The Digest contains a total of 432 titles. Titles are divided into fragments, and longer fragments are divided into paragraphs. Each fragment contains an excerpt from the work of a single jurist, with the name of the jurist and the source cited at the beginning of each.

It is customary to quote the Digests as follows: D. 8. 3. 4 (D – Digests, 8 – book, 3 – title, 4 – fragment).

The Digest’s main content consists of fragments pertaining to private law. The largest number of fragments are drawn from the works of the following jurists: Ulpian (2462), Paulus (2083), Papinian (592), Pomponius (585), Gaius (535), Julian (457), and Modestinus (345).

The Civil Code, like the Digest, is intended to regulate civil-law relations between the parties to these relations in a civilized manner and in strict compliance with the law.

Disputes arising from the negligent performance of duties by one of the parties to a civil legal relationship must be resolved by the courts. Since the time of the Roman Empire, the state has taken measures to enforce this rule.

The Digest established a rule that prohibited the use of force to restore a violated right, and its use was considered arbitrary, leading to adverse consequences. For example, a creditor who seized a debtor’s property to satisfy his claims was obligated to return the property. In doing so, he lost his right to claim it (D. 4. 2. 13). An owner who lost possession of his property and then arbitrarily took it from the actual owner was obligated to return it to the actual owner, but in doing so, he lost his right of ownership to the property (D. 8. 4. 7).

This legal norm, recorded in the Digest, was intended to make it unprofitable to resolve disputes bypassing the court.

A person’s ability to bear certain rights and obligations is now called legal capacity. Roman jurists did not have a definition of legal capacity corresponding to the modern concept, although they used the concept. Legal capacity, as a person’s ability to bear rights, arises from the moment of birth. However, Roman jurists believed that in some cases, legal capacity could arise even before a child’s birth.

The jurist Paul wrote: “Whoever is in the womb is protected as if he were among people, since the benefit of the fetus itself is at stake” (D. 1. 5. 7.). Therefore, if the father of an unborn child dies, then the share of the unborn child is taken into account when dividing the inheritance.

Roman jurists point out that in certain cases, property belongs not to individual citizens—physical persons—but to associations. Incidentally, the jurist Martian wrote: “Theaters, stadiums, and the like, for example, located in communities, belong to associations, not to individuals” (D. 18. 6. 1). Another jurist, Alphen, makes the following observation: “… even if a legion’s personnel are completely renewed over time, the legion still remains the same. The same applies to a ship on which, as a result of repairs, all its parts are replaced. It remains the same.”

Ulpian further declares: “With regard to decurions or other bodies, it makes no difference whether all remain, or only a part remains, or whether the entire composition has changed. But even if the body has been reduced to a single individual, it is generally recognized that claims can be brought against him in court, and he can bring claims in court, since the rights of all have been concentrated in one, and the name of the body remains. If there is a debt in favor of the body, then this is not a debt owed to individuals” (D. 3. 4. 1-2).

By the way, the origin of the concept of a legal entity and the definition of its main characteristics also comes from Roman law.

By Rafael Lagard

© Preems