Art, in all its manifestations, relies on fundamental building blocks that artists manipulate to create meaning, evoke emotion, and communicate ideas. These building blocks – line, shape, form, value, color, space and texture – are the elements of art.

Understanding these elements provides insight into how visual communication works and reveals the deliberate choices artists make in their creative process. Each element possesses unique characteristics and potential, yet they work in concert to produce unified works that resonate with viewers across cultures and time periods.

Line: Foundation of visual language

Line represents perhaps the most fundamental element of art, serving as the foundation upon which much of visual communication rests. At its most basic, a line is a mark made by a moving point, a continuous path that travels through space. Yet this simple definition belies the remarkable expressive range and complexity that lines can achieve.

Lines possess several defining characteristics that contribute to their communicative power. Direction gives lines their sense of movement and energy. Horizontal lines suggest calm, stability, and rest, mirroring the horizon and our reclining bodies. Vertical lines convey strength, dignity, and aspiration, recalling trees reaching skyward and the upright human figure. Diagonal lines create dynamic tension and movement, suggesting action and instability. The quality or character of a line – whether thick or thin, smooth or rough, continuous or broken – dramatically affects its emotional impact. A trembling, hesitant line communicates uncertainty or fragility, while a bold, confident stroke suggests assurance and strength.

Beyond these physical attributes, lines perform numerous functions in artistic composition. Contour lines define the edges of shapes and forms, describing where one object ends and another begins. These lines help viewers perceive and understand the boundaries of things. Cross-contour lines travel across the surface of forms, revealing their three-dimensional structure and volume. Gesture lines capture the essential movement and energy of a subject with quick, expressive marks. Implied lines exist where the eye connects separate elements, creating pathways of visual movement that guide attention through a composition.

Throughout art history, different cultures and movements have explored line’s potential in distinctive ways. Chinese brush painting elevated calligraphic line to a supreme expressive tool, where the quality of each brushstroke reveals the artist’s skill, energy, and spiritual state. Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci used line to create detailed preparatory drawings that mapped out complex compositions and explored anatomical structure. Modernists like Paul Klee experimented with line as an independent element, creating compositions where lines seem to dance and play across the picture plane with musical rhythm.

Shape: Definition of space

Shape emerges when a line encloses an area, creating a two-dimensional space with defined boundaries. Shapes are flat, possessing only height and width, and they represent one of the primary ways we organize and interpret visual information. Our brains are pattern-recognition machines, constantly identifying and categorizing shapes in our environment, making this element fundamental to how we process imagery.

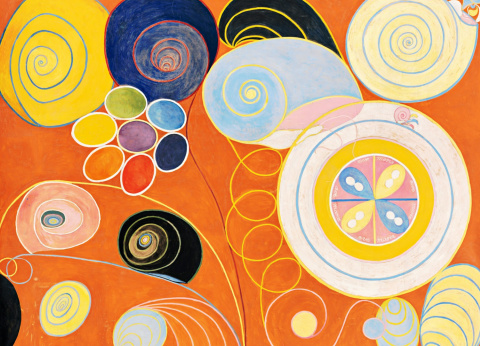

Shapes fall into two broad categories. Geometric shapes are mathematical and precise, including circles, squares, triangles and polygons. These shapes suggest order, stability, and human creation. They dominate architectural environments and designed objects, representing rationality and control. Organic shapes, conversely, are irregular and flowing, resembling forms found in nature. They suggest growth, life, and natural processes. The leaves on a tree, the outline of a cloud, or the profile of a mountain range all present organic shapes that feel vital and unpredictable.

The figure-ground relationship represents a crucial concept in understanding how shapes function. Every shape exists against some background, and our perception can shift between seeing the shape itself or the space around it. The famous optical illusion of the vase and faces illustrates this phenomenon – the same image can be perceived as either a white vase against a black background or two black faces in profile against white space. Artists manipulate figure-ground relationships to create visual interest, ambiguity, or emphasis.

Positive shapes are the primary subjects or objects in a composition, the things we typically focus on first. Negative shapes are the spaces between and around those subjects. Sophisticated compositions treat negative space with as much care as positive shapes, recognizing that the empty areas contribute crucially to overall design. Japanese aesthetics particularly emphasize the importance of ma, the meaningful void, where negative space becomes an active element rather than mere emptiness.

Shape also carries symbolic and psychological associations. Circles suggest wholeness, unity, and infinity, having no beginning or end. They appear in religious and spiritual imagery across cultures, from halos to mandalas. Triangles create dynamic tension and can suggest either stability when base-down or instability when inverted. Squares and rectangles convey solidity, honesty, and rationality. These associations aren’t arbitrary but arise from our physical experience of these forms and their presence in our environment.

Form: The third dimension

Form extends shape into three-dimensional space, adding depth to height and width. While shape is flat, form possesses volume and occupies actual space. This element becomes particularly relevant in sculpture, architecture, and three-dimensional design, though painters and photographers also create the illusion of form on their two-dimensional surfaces.

Like shapes, forms can be geometric or organic. Geometric forms include spheres, cubes, cylinders, cones, and pyramids – the basic building blocks of three-dimensional design. These forms can be combined and modified to create more complex structures. Organic forms are irregular and flowing, like those found in natural objects, living creatures, and weathered rocks. The human body itself is an organic form of extraordinary complexity, which explains why figure drawing and sculpture have remained central challenges throughout art history.

Creating the illusion of form on a flat surface requires various techniques. Shading and modeling use gradations of light and dark to suggest volume and three-dimensionality. Artists observe how light falls on forms, noting areas of highlight, midtone, core shadow, reflected light, and cast shadow. Capturing these tonal variations convinces the eye that a flat surface contains depth. Overlapping, where one form partially obscures another, provides another depth cue, suggesting spatial relationships. Atmospheric perspective, where distant forms appear lighter, bluer, and less distinct, creates an illusion of deep space.

The actual three-dimensional forms created by sculptors exist in real space and can be viewed from multiple angles. Relief sculptures project from a background surface, maintaining some connection to two-dimensional design. Low relief barely rises from the background, while high relief projects dramatically. Freestanding sculpture, also called sculpture in the round, can be circumnavigated and viewed from all sides, creating an experience that unfolds over time as the viewer moves.

Mass and volume represent related but distinct concepts in understanding form. Mass refers to the physical bulk or weight of a form, its density and solidity. Volume describes the amount of space a form occupies, which can be perceived as either solid or hollow. Henry Moore’s reclining figures play with these concepts, creating massive bronze sculptures pierced by voids that allow space to flow through the forms, challenging our expectations about weight and solidity.

Value: Language of light

Value describes the relative lightness or darkness of a color or tone, ranging from pure white through various grays to absolute black. This element proves crucial for creating the illusion of light, establishing mood, and organizing composition. Value often operates somewhat invisibly – we might first notice color or subject matter – but it provides the underlying structure that makes images readable and emotionally resonant.

A value scale arranges tones from lightest to darkest, typically showing seven to nine distinct steps, though an infinite gradation exists between extremes. Artists train themselves to perceive these subtle distinctions, learning to see not just local color but tonal relationships. A red apple isn’t simply red but contains a range of values from highlighted areas catching direct light to shadowed regions where form turns away from the light source.

Value performs several critical functions in visual art. It creates the illusion of three-dimensional form through shading and modeling, as discussed earlier. The careful gradation of values across a surface convinces us we’re seeing volume rather than flatness. Value also establishes spatial depth, with stronger contrasts typically appearing in foreground areas while reduced contrast suggests distance. Atmospheric haze in the environment causes this phenomenon, which artists exploit to create convincing space.

The emotional and dramatic impact of value cannot be overstated. High-key compositions, dominated by light values, often feel airy, optimistic, or ethereal. Low-key compositions, emphasizing dark values, create drama, mystery, or somber moods. Film noir cinematography masterfully exploits low-key lighting and high contrast to generate psychological tension and moral ambiguity. Chiaroscuro, the dramatic use of strong value contrasts, became a signature technique during the Baroque period, particularly in the work of Caravaggio, who used powerful light and shadow to heighten emotional intensity and focus attention.

Value contrast serves as one of the most effective tools for creating emphasis and visual hierarchy. Our eyes naturally gravitate toward areas of highest contrast, where light and dark values meet most dramatically. Designers and artists place important elements in these high-contrast zones to ensure they capture attention. Conversely, areas of similar value recede, allowing them to serve supporting roles in composition.

Interestingly, value often proves more important than color for recognition and readability. When we squint at an image or view it in dim light, color information diminishes but value relationships remain visible. This explains why successful compositions typically possess strong value structures that work even when viewed in grayscale. Many artists create preliminary value studies, planning tonal organization before introducing the complexity of color.

Color: The emotional powerhouse

Color stands as perhaps the most immediately striking and emotionally powerful element of art. It possesses the unique ability to evoke visceral responses, influence mood, and carry cultural meanings. The physics of color involves wavelengths of light, but our experience of color is deeply psychological and cultural, making it both a scientific and subjective phenomenon.

Understanding color requires familiarity with several organizing concepts. The color wheel arranges hues in a circular spectrum, showing relationships between colors. Primary colors – red, yellow, and blue in traditional pigment theory – cannot be created by mixing other colors but serve as the basis for all other hues. Secondary colors – orange, green, and violet – result from mixing two primaries. Tertiary colors emerge from combining primary and secondary colors, creating red-orange, yellow-orange, yellow-green, blue-green, blue-violet, and red-violet.

Color possesses three fundamental properties. Hue is the name of the color itself, its position on the color wheel. Value, as discussed earlier, describes how light or dark the color appears. Saturation, also called intensity or chroma, indicates the purity or vividness of a color. A highly saturated color appears vivid and pure, while a desaturated color appears grayed and muted. These three properties can be adjusted independently, allowing infinite variations within color space.

Color relationships create different effects in composition. Complementary colors sit opposite each other on the color wheel – red and green, blue and orange, yellow and violet. When placed adjacent to each other, complements create maximum contrast and visual vibration. Analogous colors sit next to each other on the wheel, creating harmonious, related color schemes. Triadic color schemes use three colors equally spaced around the wheel, creating balanced diversity. Monochromatic schemes explore variations of a single hue through different values and saturations.

Temperature represents another crucial color characteristic. Warm colors – reds, oranges, yellows – are associated with fire, sun, and heat. They tend to advance visually and feel energizing or aggressive. Cool colors – blues, greens, violets – evoke water, sky, and coolness. They typically recede visually and feel calming or melancholy. Artists exploit color temperature to create spatial effects and emotional atmospheres. Impressionist painters observed that shadows aren’t merely darker versions of local color but contain cool, reflected light, leading them to paint shadows with blues and violets rather than just adding black.

Color carries powerful symbolic and cultural associations, though these vary across societies. White suggests purity and innocence in Western cultures but mourning in some Eastern traditions. Red can signify passion, danger, luck, or revolution depending on context. Blue might represent sadness, tranquility, masculinity, or divinity. These associations aren’t inherent to the colors themselves but learned through cultural experience, making color interpretation complex and context-dependent.

Psychological responses to color have been studied extensively, though individual reactions vary. Warm colors generally increase arousal and energy levels. Cool colors tend to be calming and can even lower heart rate and blood pressure. Certain colors affect our perception of space, time, and weight – rooms painted in light colors seem more spacious, and boxes in lighter colors feel lighter to lift. Marketing and design fields exploit these psychological effects, though artists use them more subtly to enhance emotional content and guide viewer experience.

Space: Illusion of depth

Space encompasses the area around, between, and within objects. In three-dimensional art like sculpture and architecture, space is literal and physical. In two-dimensional art like painting and drawing, artists create the illusion of space through various techniques, convincing viewers that a flat surface contains depth and distance.

Positive space contains the subjects and objects of a composition, the areas of primary focus. Negative space, as mentioned earlier, comprises the areas around and between subjects. Sophisticated spatial design considers both equally, recognizing that negative space shapes our perception of positive elements and contributes to overall composition. Japanese garden design demonstrates this principle beautifully, where carefully placed rocks and plants shape the surrounding emptiness into meaningful spatial relationships.

Creating pictorial space on a two-dimensional surface represents one of art’s great achievements. Linear perspective, systematized during the Italian Renaissance, uses geometric principles to create convincing spatial illusion. One-point perspective features a single vanishing point on the horizon line where parallel lines converge, often used for views straight down streets or corridors. Two-point perspective employs two vanishing points for objects viewed at an angle. Three-point perspective adds a third vanishing point above or below, useful for dramatic views looking up at buildings or down from heights.

Atmospheric or aerial perspective creates depth through changes in clarity, value, and color. Distant objects appear lighter, bluer, and less detailed due to atmospheric haze. Leonardo da Vinci described this effect and exploited it masterfully in paintings like the Mona Lisa, where the distant landscape fades into soft, bluish obscurity. This technique proves particularly effective for suggesting vast distances in landscape painting.

Overlapping provides one of the simplest depth cues – when one form obscures another, we immediately understand spatial relationships. Size differences also suggest space, as we expect distant objects to appear smaller than near objects of similar size. Placement on the picture plane matters too, with objects higher in the composition typically understood as farther away, while those lower seem closer.

The picture plane itself represents an important concept – the flat, two-dimensional surface on which the image exists. Artists can emphasize this flatness, acknowledging the work’s material reality, or work to deny it, creating windows into illusionistic space. Modernist movements like Abstract Expressionism often celebrated the picture plane’s flatness, rejecting traditional illusion in favor of acknowledging painting’s physical reality. Conversely, trompe l’oeil paintings aim to deceive viewers into believing painted elements are real three-dimensional objects.

Shallow space compresses depth, keeping most elements within a narrow zone parallel to the picture plane. Medieval and Byzantine art often employed shallow space, creating decorative, patterned compositions where spiritual concepts mattered more than naturalistic representation. Deep space creates the illusion of vast distances receding far from the picture plane. Baroque ceiling paintings often feature dramatic deep space, depicting clouds, angels, and heavenly architecture soaring overhead in vertiginous illusion.

Texture: The tactile dimension

Texture refers to the surface quality of objects, how they feel or appear they would feel if touched. This element engages our tactile sense, even when experienced purely visually, connecting art to physical, embodied experience. Texture adds richness and interest to surfaces, providing another layer of information and sensory engagement.

Actual texture, also called tactile or physical texture, exists in three-dimensional reality. Sculpture, craft objects, and architectural surfaces possess textures we can physically feel -the roughness of stone, the smoothness of polished bronze, the grain of wood, the softness of fabric. Contemporary art often emphasizes actual texture, incorporating unconventional materials and celebrating their tactile properties. Assemblage and mixed-media works exploit texture deliberately, creating surfaces that demand both visual and imaginative tactile attention.

Implied or visual texture simulates texture on a smooth surface through skillful rendering. Painters create the illusion of various textures -weathered wood, soft fur, translucent fabric, rough bark – using only paint on flat canvas. This requires careful observation and technical skill, capturing the visual patterns that characterize different surfaces. Hyper-realistic painters take this to extremes, creating paintings where implied textures are nearly indistinguishable from the real thing.

Pattern relates closely to texture but represents a more organized repetition of elements. Patterns can be geometric or organic, regular or irregular. Decorative arts and design traditions worldwide have developed sophisticated pattern vocabularies, from Islamic geometric patterns to Arts and Crafts wallpaper designs. Pattern can function decoratively, flattening space and emphasizing surface, or it can help define form and suggest texture.

Artists manipulate texture for various purposes. Smooth textures suggest refinement, sleekness, or artificiality. Rough textures convey rawness, natural processes, or age. Varied textures within a composition create visual interest and can help differentiate forms and materials. Impasto painting, where paint is applied thickly so brushstrokes remain visible and even protrude from the surface, celebrates texture as an expressive element itself. Van Gogh’s later paintings exemplify this approach, with swirling, built-up paint creating intense physical presence and emotional energy.

Texture affects light reflection and absorption, influencing how we perceive color and value. Matte surfaces absorb light, appearing darker and less saturated. Glossy surfaces reflect light, creating highlights and appearing brighter. This interaction between texture and light contributes to our perception of materials and spatial relationships.

Integration of elements

While analyzing each element individually provides useful understanding, actual artworks integrate multiple elements working together to create unified effects. A successful composition orchestrates line, shape, form, value, color, space, and texture into a coherent whole where each element supports and enhances the others.

Consider how these elements interact in a Renaissance painting. Linear perspective creates convincing space, while careful value modeling gives forms three-dimensional presence. Color is used harmoniously but also expressively, with significant figures often wearing saturated hues that command attention. Lines define edges and guide the eye through compositional pathways. Implied textures differentiate materials – the smoothness of skin, the shine of silk, the roughness of stone. Each element is handled masterfully, but their integration creates something greater than the sum of parts.

Different artistic movements and cultural traditions emphasize elements differently. Classical Greek sculpture prioritized form, seeking ideal proportions and three-dimensional beauty. Chinese landscape painting elevated line to supreme importance while creating distinctive spatial organizations. Impressionism revolutionized color theory, fragmenting hues and exploring optical effects. Minimalism reduced elements to essential forms, lines, and colors. These varying emphases demonstrate that while the elements remain constant, their potential applications are limitless.

Understanding these elements benefits not just artists but anyone who wishes to look at art more deeply. Recognizing how line creates movement, how value structures composition, how color evokes emotion, or how space is manipulated allows for richer engagement with visual culture. These elements form a grammar of visual communication, a set of tools for encoding and decoding meaning in images.

The elements of art represent fundamental aspects of visual experience, refined and codified through centuries of artistic practice and theoretical reflection. They provide artists with a toolkit for expression and viewers with a framework for understanding.

Whether creating or appreciating art, familiarity with these elements deepens engagement and reveals the sophisticated decisions underlying even seemingly simple images. From prehistoric cave paintings to contemporary digital art, these same elements continue to organize and empower visual communication, demonstrating their enduring relevance to human expression.

By Leon Oren

© Preems