London’s black cabs are more than just a mode of transport – they’re rolling symbols of the city’s grit, history and unyielding charm. With their distinctive boxy shape, tight turning circles and drivers armed with an encyclopedic “Knowledge” of the streets, these vehicles have ferried everyone from royalty to rowdy tourists through fog-shrouded alleys and bustling thoroughfares.

The story of London’s taxis begins with hooves clattering on cobblestones. The term “hackney carriage” dates back to the early 17th century, derived from the French word hacquenée, meaning a horse for hire. The first documented public hackney coach service appeared in London around 1605, when enterprising innkeepers began renting out carriages to weary travelers. By 1625, these services had grown popular enough that regulations were introduced to curb chaotic competition.

A pivotal moment came in 1636 when Captain John Baily, a retired naval officer, established London’s first official taxi rank outside the Maypole Inn on The Strand. He outfitted four hackney coaches in a uniform livery and set strict rules for his drivers, including fixed fares and proper conduct – laying the groundwork for the professional standards that persist today. These early cabs were cumbersome four-wheeled affairs, often pulled by two horses, and catered to the emerging middle class navigating the expanding metropolis.

The 19th century brought innovation with the introduction of the hansom cab in 1834, designed by architect Joseph Hansom. This sleek, two-wheeled vehicle was lighter, faster and more maneuverable, with the driver perched high at the rear for a bird’s-eye view.

Hansoms became synonymous with Victorian London, immortalized in Sherlock Holmes stories where they whisked detectives through gas-lit streets. However, they weren’t without drama: accidents were common, and fares were calculated using early mechanical meters, leading to the term “taximeter” (from the French taxe, meaning charge). By the mid-1800s, over 11,000 hackney carriages plied London’s roads, but horse manure and traffic jams hinted at the need for change.

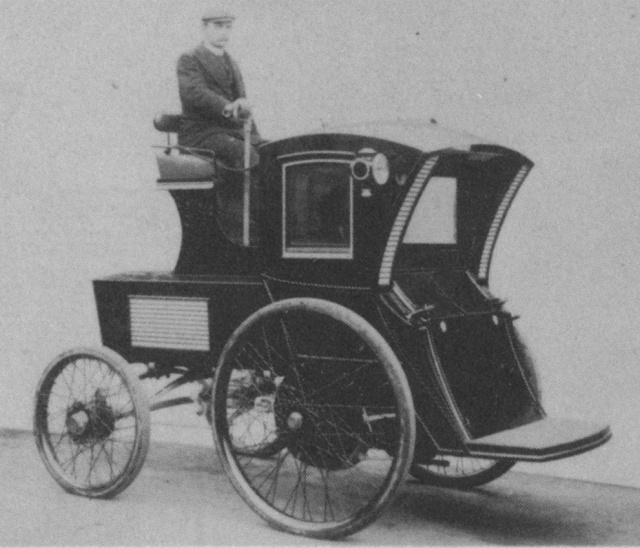

The turn of the 20th century marked the shift from equine to engine power. In 1897, entrepreneur Walter Bersey introduced the first electric taxis, dubbed “hummingbirds” for their quiet buzz. His fleet of 12 Bersey Electric Cabs promised a cleaner, smoother ride, but battery limitations and high costs doomed them after just two years.

Petrol-powered taxis soon took over. The first motorized cab hit London’s streets in 1903 – a French-built Prunel, followed by British models like the Unic, which became wildly popular by 1907 with its reliability and range. Post-World War I, companies like William Beardmore & Company innovated with purpose-built taxis, emphasizing durability for the city’s potholed roads.

The true icon emerged after World War II with the Austin FX3 in 1948, featuring a distinctive rounded bonnet and spacious interior. Its successor, the FX4 (1958-1997), solidified the “black cab” archetype: painted black for uniformity (though not mandatory – early ones came in various colors), with a partition separating driver and passengers, and a legendary 25-foot turning circle to navigate tight medieval streets like those around the Tower of London. This turning radius, mandated by regulations, allows cabs to U-turn in spaces where most cars would stall, a feature born from the need to enter narrow Savoy Hotel forecourts.

By the 1980s, models like the Fairway and TX series refined the design, adding wheelchair accessibility – a world-first for taxis – and features like intercoms and climate control. These cabs weren’t just vehicles; they were mobile fortresses of British engineering, capable of lasting over 500,000 miles.

No discussion of London taxis is complete without “The Knowledge,” the grueling exam that turns aspiring drivers into human GPS systems. Introduced in 1865 by the Metropolitan Police to ensure safety and efficiency, it requires memorizing 320 routes (“runs”), 25,000 streets, and 20,000 landmarks within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross.

The process takes 2-4 years, involving “appearances” – oral exams where candidates recite the shortest, most logical path between points while accounting for traffic, one-way streets, and even hospital entrances. Trainees, often on mopeds with maps strapped to handlebars, crisscross the city in all weather, a rite of passage that’s as much mental marathon as geographical gauntlet.

Fascinatingly, science backs its rigor: MRI studies show that successful cabbies have enlarged posterior hippocampi, the brain region for spatial memory, proving that The Knowledge literally rewires the mind. In an era of sat-navs, this tradition endures, setting black cab drivers apart from app-based rivals. As one veteran cabbie quipped, “Google Maps doesn’t know the shortcuts during rush hour – or the best pub for a pit stop.”

The 21st century has electrified London’s taxi scene – literally. In 2018, the London Electric Vehicle Company (LEVC), owned by Chinese firm Geely, launched the TX eCity, a plug-in hybrid black cab with a 70-mile electric range and zero-emission mode for central London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone. By 2025, over half of the 19,000 black cabs are electric or hybrid, reducing the fleet’s carbon footprint amid the city’s push for net-zero by 2030. These modern marvels retain the classic look but add USB ports, panoramic roofs and even contactless payment.

But the rise of Uber in 2012 disrupted the industry, offering cheaper, app-summoned rides. Black cab drivers protested vehemently, staging “go-slows” that gridlocked Trafalgar Square, arguing that unregulated private hires undercut their standards. Today, Uber has expanded its EV fleet in London, funding 700 charging points and aiming for all-electric by 2025, but black cabs counter with hail-ability, bus lane access, and The Knowledge’s edge in efficiency.

Looking forward, autonomous tech looms – Uber plans robotaxi trials in London by spring 2026 – but traditional cabs emphasize human touch. With regulations tightening, the fleet could go fully electric by 2030, blending heritage with high-tech.

London’s black cabs transcend transport; they’re cultural touchstones. In films like “The Bourne Identity or Sherlock Holmes,” they zip through chases, embodying the city’s pulse. TV shows such as “The Knowledge” documentary highlight drivers’ wit, while literature from Charles Dickens to modern thrillers features them as confidants or getaway vehicles.

For tourists, hailing a black cab is a rite: the spacious interior fits luggage and families, and drivers often double as impromptu tour guides, sharing tales of hidden gems. They’re as emblematic as Big Ben or red buses, appearing on postcards, toys, and even wedding transports for a touch of elegance. In popular culture, cabbies represent London’s no-nonsense spirit – chatty, opinionated, and always ready with a route or a rant.

From 17th-century hackneys to sleek electric TXs, London’s taxis have mirrored the city’s evolution: resilient, adaptive and quintessentially British. Facing digital disruptors and environmental imperatives, they continue to thrive on tradition and innovation. Next time you flag one down on a rainy Oxford Street, remember – you’re not just getting a ride; you’re stepping into four centuries of history.

By James Fuller, London

© Preems

One comment