The Bronx, one of New York City’s five boroughs, has undergone a remarkable evolution over centuries. Once synonymous with urban decay and hardship, it is now emerging as a vibrant, modern area with improved housing, economic opportunities, and cultural vitality.

The Bronx’s story begins long before its incorporation into New York City. The area was originally inhabited by the Lenape Native American people, specifically the Siwanoy band, who called the region part of Lenapehoking.

European colonization started in 1639 when Jonas Bronck, a Swedish-born sea captain under Dutch employ, established the first European settlement in the area as part of New Netherland. The land was named “Bronck’s Land,” which eventually evolved into “the Bronx.” Over the following decades, the area was developed into farmlands by European colonists, displacing indigenous populations.

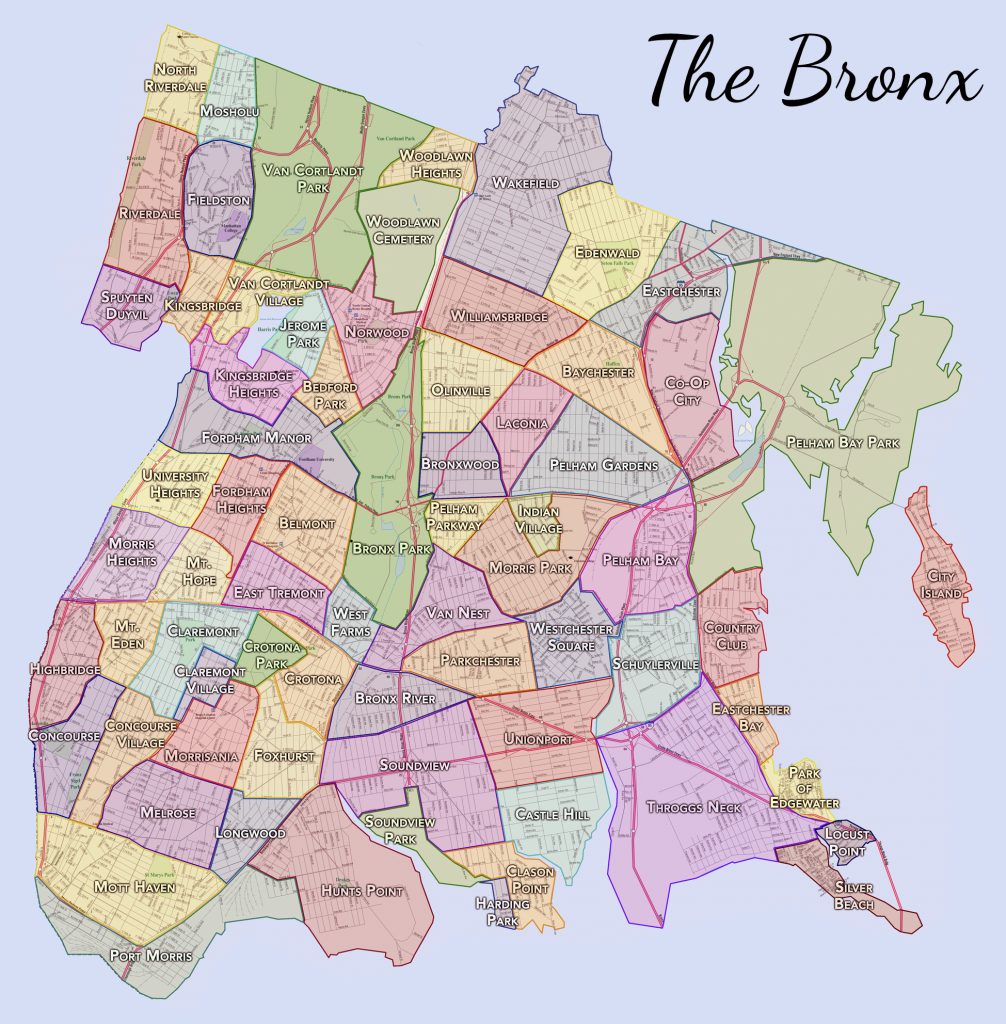

In the 19th century, the Bronx was part of Westchester County. Its integration into New York City occurred in stages: the western portion was annexed in 1874, followed by the eastern areas in 1895. This annexation was driven by urban expansion needs, including improved transportation links. Bronx County was officially separated from New York County (Manhattan) in 1914, making it the last of New York State’s 62 counties to be incorporated.

The early 20th century marked a period of rapid growth. The extension of subway lines to the Bronx in 1904 spurred a population boom, attracting waves of immigrants, including Irish, Italians, and Jews. From 200,000 residents in 1900, the population surged to 1.3 million by 1930. The borough became a hub for manufacturing, particularly pianos, and hosted events like the 1918 World’s Fair. Iconic landmarks such as Yankee Stadium (opened in 1923) and the Bronx Zoo solidified its cultural identity.

Post-World War II, demographic shifts began. Moderate- and upper-income non-Hispanic White residents started relocating to suburbs, a phenomenon known as “white flight,” altering the borough’s social fabric.

The Bronx’s transformation narrative includes a dark chapter of decline from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, particularly in the South Bronx. Factors such as the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, which displaced communities, high-rise public housing projects that isolated residents, redlining by banks, and reduced municipal services contributed to urban blight.

A wave of arson in the 1970s, often perpetrated by landlords for insurance payouts, devastated neighborhoods. Seven census tracts lost over 97% of their buildings between 1970 and 1980, and the South Bronx saw a 60% population drop and 40% loss of housing units. The phrase “The Bronx is burning” became infamous during the 1977 World Series blackout, symbolizing the borough’s struggles with crime, poverty, and decay.

Areas like Melrose exemplified this downturn. Once a thriving immigrant enclave with tenements and elevated rail lines, it suffered from post-WWII middle-class exodus, fiscal crises, and the removal of the Third Avenue Elevated in the 1970s, leading to vacant lots, drugs, and violence by the 1980s.

Revitalization began in the late 1980s, driven by community activism and government initiatives. Mayor Ed Koch’s “Ten-Year Housing Plan” stimulated new construction, replacing burned-out tenements with affordable units. By 2007, over 33,000 new residential units were built or underway, with $4.8 billion invested.

Key projects include the Lambert Houses, completed in 1973 as part of the Bronx Park South Urban Renewal Area, which provided innovative low-income housing and served as a model for inner-city redevelopment. In Melrose, the Nos Quedamos committee, formed in the early 1990s, prevented displacement and collaborated on the 1994 Melrose Commons Urban Renewal Plan, emphasizing mixed-income housing, sustainability, and community spaces. This led to over 3,300 new units, including affordable senior housing and cultural sites like the Bronx Music Heritage Center.

Broader efforts include the Bronx Civic Center Downtown Revitalization Initiative (2018), which aimed to create vibrant neighborhoods through mixed-use developments. Recent projects, such as the reconstruction of Yankee Stadium and new Metro-North stations, have improved connectivity. In 2024, the Morris Park neighborhood plan was approved, promising 7,000 homes and 10,000 jobs. Community gardens and casitas have transformed vacant lots into green spaces, fostering social cohesion.

These initiatives have shifted the Bronx from a symbol of decline to one of resilience, with investments in retail (e.g., Bronx Terminal Market) and cultural venues attracting residents and visitors.

As of 2025, the Bronx is home to approximately 1.42 million people, with a diverse demographic: 54.8% Hispanic, 33.1% Black, and a significant foreign-born population (35.3%). It remains the third-most densely populated county in the U.S., but revitalization has made it more comfortable.

The Bronx contributes to NYC’s record-high employment, with a GDP of $43.7 billion in 2022. Consumer spending rose 7% above 2019 levels by March 2024, driven by retail districts like Fordham Road and The Hub. However, it hosts the poorest congressional district (NY-15), with a median household income of $36,593 and high poverty rates. Affordable housing production is concentrated here, with 562,300 units (15% of NYC’s total). Initiatives like Borough President Vanessa Gibson’s 2025 State of the Borough address focus on economic growth and investments.

The Bronx is a cultural powerhouse, birthplace of hip-hop in the 1970s (thanks to DJ Kool Herc) and Latin jazz. Attractions include the Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx Opera, and events like Bronx Week. Its diversity—over 59% speak non-English at home—fuels a vibrant scene of Caribbean, African, and Latin American influences.

Crime rates have improved, with a serious crime rate of 20.1 per 1,000 residents in 2024, higher than the city average of 13.6. However, satisfaction remains low: only 36% of residents rate their neighborhood as excellent or good, and 24% approve of overall quality of life – the lowest in NYC. Subway safety concerns persist, with 53% feeling safe in parks during the day. Measures like the 2025 Bodega Act aim to enhance store security with panic buttons and grants.

Looking ahead, the Bronx’s transformation continues with projects like the Kingsbridge Armory redevelopment and expanded transit. Challenges like affordability (76% of New Yorkers cite it as a reason to leave) and persistent poverty require ongoing efforts.

The Bronx’s journey from indigenous lands to a modern borough exemplifies urban resilience. Through history’s trials and community-led renewals, it has become a more comfortable, inclusive place – proving that with investment and vision, transformation is possible.

By Paula Meinard, New York

© Preems